Despite the theory that everything can be done in software (and of course, anything that can’t be done could in principle be approximated using numerical methods, or fudged using machine learning), software engineering itself, the business of writing software, seems to be full of tools that are accepted as de facto standards but, nonetheless, begrudgingly accepted by many teams. What’s going on? Why, if software is eating the world, hasn’t it yet found an appealing taste for the part of the world that makes software?

Let’s take a look at some examples. Jira is very popular among many people. I found a blog post literally called Why I Love Jira. And yet, other people say that Jira is an anti pattern, a sentiment that gets reasonable levels of community support.

Jenkins is almost certainly the (“market”, though it’s free) leader among continuous delivery tools, a position it has occupied since ousting Hudson, from which it was forked. Again, it’s possible to find people extolling the virtues and people hating on it.

Lastly, for some quantitative input, we can find that according to the Stack Overflow 2018 survey, most respondents (78.9%) love Rust, but most people use JavaScript (69.8%). From this we draw the interesting conclusion that the most popular tool in the programming language realm is not, actually, the one that wins the popularity contest.

So, weird question, why does everybody do this to themselves? And then more specifically, why is your team doing it to yourselves, and what can you do about it?

My hypothesis is that all of these tools succeed because they are highly configurable. I mean, JavaScript is basically a configuration language for Chromium (don’t @ me) to solve/cause your problem. Jira’s workflows are ridiculously configurable, and if Jenkins doesn’t do what you want then you can find a plugin to do it, write a plugin to do it or make a Groovy script that will do it.

This appeals to the desire among software engineers to find generalisations. “Look,” we say, “Jenkins is popular, it can definitely be made to do what we want, so let’s start there and configure it to our needs”.

Let’s take the opposing view for the moment. I’m going to drop the programming language example of JS/Rust, because all programming languages are, roughly speaking, entirely interchangeable. The detail is in the roughness. The argument below still applies, but requires more exposition which will inevitably lead to dissatisfaction that I didn’t cover some weird case. So, for the moment, let’s look at other tools like Jira and Jenkins.

The exact opposing view is that our project is distinct, because it caters to the needs of our customers and their (or these days, probably our) environment, and is understood and worked on by our people with our processes, which is not true for any other project. So rather than pretend that some other tool fits our needs or can be bent into shape, why don’t we build our own?

And, for our examples, building such a tool doesn’t appear to be a big deal. Using the expansive software engineering term “just”, a CD tool is “just” a way to run each step in the deployment pipeline and tell someone when a step fails. A development-tracking tool is “just” a way to list the things the team is or could be working on.

This is more or less a standard “build or buy” question, with just one level of indirection: both building and buying are actually measured in terms of time. How long would it take the team to write a new CD tool, and to maintain it? How long would it take the team to configure Jenkins, and to maintain it?

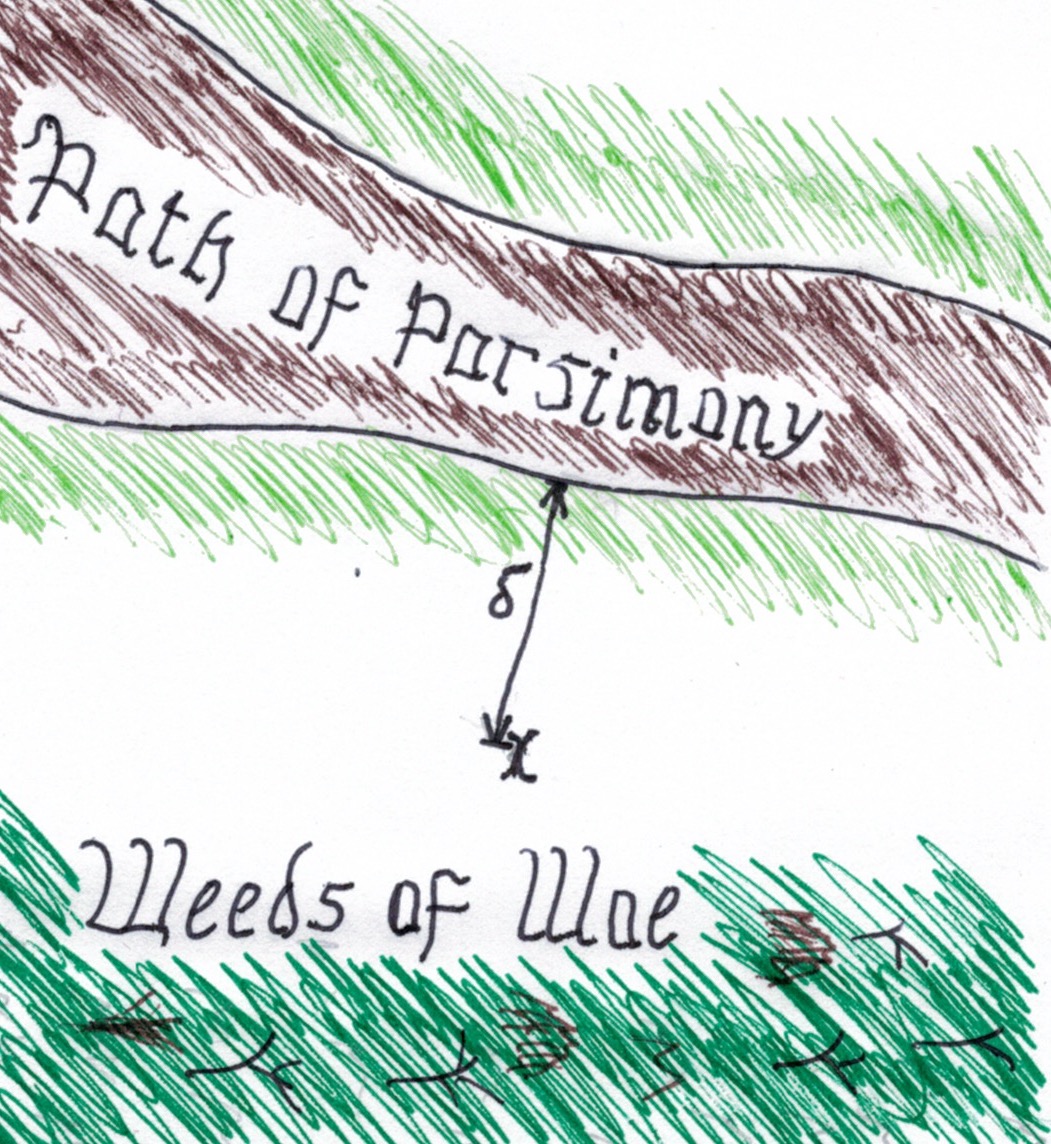

The answer should be fairly easy to consider. Let’s look at the map:

We are at x, of course. We are a short way from the Path of Parsimony, the happy path along which the generic tools work out of the box. That distance is marked on the map as ∂.

Think about how you would measure ∂ for your team. You would consider the expectations of the out-of-the-box tool. You would consider the expectations of your team, and of your project. You would look at how those expectations differ, and try to quantify the result.

This tells you something about the gap between what the tool provides by default and what you need, which will help you quantify the amount of customisation needed (the cost of building a spur out from the Path of Parsimony to x). You can then compare that with the cost of building a tool that supports your position directly (the cost of building your own path, running through x).

But the map also suggests another option: why don’t we move from x closer to the path, and make ∂ smaller? Which of our distinct assumptions are incidental and can be abandoned, which are essential and need to be supported, and which are historical and could be revised? Is there a way to change the context so that adopting the popular tool is cheaper?

[Left out of the map but just as important is the related question: has somebody else already charted a different path, and how far are we from that? In other words, is there a different off-the-shelf product which needs less configuration than the one we’ve picked, so the total migration-plus-configuration cost is less than sticking where we are?]

My impression is that these questions tend to get asked once at the start of a project or initiative, then not again until the team is so far away from the Path of Parsimony that they are starting to get tangled and stung by the Weeds of Woe. Teams that change tooling such as their issue trackers or CD pipeline tend to do it once the existing way is already hurting too much, and the route back to the path no longer clear.